This month’s Under-Appreciated Rock Band, HOLLIS BROWN is not a person, but the name of a band. It is taken from the name of a Bob Dylan song, “Ballad of Hollis Brown”.

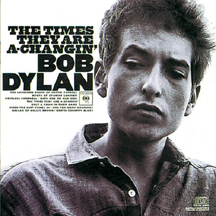

“Ballad of Hollis Brown” is on Dylan’s third album, The Times They Are A-Changin’, and I imagine that this is the album that most people think is his most overtly “protest” album. I beg to differ; Dylan’s breakthrough second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan includes four songs that are much closer to being protest songs than any of the songs on Times: “Blowin’ in the Wind”, “Masters of War”, “Oxford Town”, and “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”.

In fact, I would go so far as to say that Bob Dylan is much less of a protest singer than he is generally perceived to be. I speak as someone who is as big a fan of the acoustic Dylan as of the electric Dylan, and I own dozens of songs from this time period that never made it onto any of Bob Dylan’s major-label albums – and there are hardly any protest songs among those recordings either.

I dare say that I was one of the few Dylan fans who was disappointed when The Basement Tapes came out. I eagerly put on the supposed legitimate release of the classic double-LP bootleg album Great White Wonder, only to find that not a single one of the great early acoustic songs that made up most of that album were present; it was all electric songs that Bob Dylan recorded with The Band at the famous Big Pink house (and honestly, there weren’t all that many of them on Great White Wonder).

To return to the topic at hand, “Ballad of Hollis Brown” is much more typical of the kind of truly wonderful song that Dylan was doing in those days: social commentary, and not protest. The song is based on a true story of a South Dakota farmer named Hollis Brown; desperately poor and at the end of his rope, he kills his wife, his children and then himself. As taken from Wikipedia, critic David Horowitz writes of this too-little-known Dylan classic:

“Technically speaking, ‘Hollis Brown’ is a tour de force. For a ballad is normally a form which puts one at a distance from its tale. This ballad, however, is told in the second person, present tense, so that not only is a bond forged immediately between the listener and the figure of the tale, but there is the ironic fact that the only ones who know of Hollis Brown’s plight, the only ones who care, are the hearers who are helpless to help, cut off from him, even as we in a mass society are cut off from each other.”

* * *

Generally speaking, politicians (and even “the Establishment”) are rarely in Bob Dylan’s sights. As an example, “Oxford Town” was written in direct response to an invitation from Broadside magazine for folk singers to write a song about the black student, James Meredith who enrolled at the University of Mississippi on October 1, 1962. That’s about as close to a pure protest song as anything Dylan ever wrote. However, I imagine that most people living outside the state of Mississippi have no idea that “Ole Miss” is located in the city of Oxford, and Dylan never mentions the student or the university. In a 1963 interview with Studs Terkel, Bob Dylan talked about “Oxford Town”: “It deals with the Meredith case, but then again it doesn’t. . . . I wrote that when it happened, and I could have written that yesterday. It’s still the same. ‘Why doesn’t somebody investigate soon’ – that.s a verse in the song.”

About “Blowin’ in the Wind”, Bob Dylan’s most famous song along these lines, I can hardly improve on what Wikipedia has to say: “Although it has been described as a protest song, it poses a series of rhetorical questions about peace, war and freedom. The refrain ‘The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind’ has been described as ‘impenetrably ambiguous: either the answer is so obvious it is right in your face, or the answer is as intangible as the wind’”.

As to the other protest songs on Freewheelin’, Dylan’s angriest song by far, “Masters of War” is directed not at the politicians who get us into wars, but at the war-machine corporations who profit from them. Dylan states in the liner notes on the album: “I’ve never written anything like that before. I don’t sing songs which hope people will die, but I couldn’t help it with this one. The song is a sort of striking out . . . a feeling of what can you do?”. More than any other song that I can think of, in later years Bob Dylan dramatically altered the arrangement of “Masters of War” in concert performances to the point that it is almost unrecognizable from the original version.

In a 2001 interview published in USA Today, Bob Dylan linked this song to the famous farewell address by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on January 17, 1961: “‘Masters of War’ . . . is supposed to be a pacifistic song against war. It’s not an anti-war song. It’s speaking against what Eisenhower was calling a military-industrial complex as he was making his exit from the presidency. That spirit was in the air, and I picked it up.”

The most complex and imaginative of these songs, “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” is sometimes mistakenly linked with the Cuban Missile Crisis; but actually, Bob Dylan had already written the song before the crisis happened. In the liner notes on the album, Dylan famously spoke of this song: “Every line in it is actually the start of a whole new song. But when I wrote it, I thought I wouldn’t have enough time alive to write all those songs so I put all I could into this one.” Author Ian MacDonald described “A Hard Rain” as one of the most idiosyncratic protest songs ever written.

In the Studs Terkel interview mentioned above, Dylan uncharacteristically laid out what he meant by some of the lyrics in “Hard Rain”: “No, it’s not atomic rain, it’s just a hard rain. It isn’t the fallout rain. I mean some sort of end that’s just gotta happen. . . . In the last verse, when I say, ‘the pellets of poison are flooding the waters’, that means all the lies that people get told on their radios and in their newspapers.”

* * *

On the following album, The Times They Are A-Changin’, the targets are even more diffuse. A careful listen to the title song, “The Times They Are A-Changin’” makes it clear that Bob Dylan is not sending out some clarion call for protest and change, although the tone of the song makes it seem that way. The lyrics are an acknowledgement that the train has already left the station – that the world has irrevocably changed – along with a warning to those who haven’t gotten it yet.

“With God on Our Side” relates a litany of various wars, the Cold War and other historical events – such as the slaughter of Native Americans in the 19th Century and the Holocaust – in the context of the oft-believed notion that God or some other higher power is “with us”. Tellingly, nothing is said about the Vietnam War at all in the song originally, although a verse was added for live performances in the 1980’s. I had never heard that before, and I doubt you had either; here is the added verse: “In the nineteen-sixties came the Vietnam War / Can somebody tell me what we’re fightin’ for? / So many young men died / So many mothers cried / Now I ask the question / Was God on our side?”

“Only a Pawn in Their Game” is about the murder (Wikipedia calls it an “assassination”, and that is not really an overstatement) of civil rights activist Medgar Evers in his own driveway. The conviction of the unrepentant Klansman Byron de la Beckwith for the murder took place in Mississippi in 1994; two other trials of this man 30 years earlier resulted in hung juries. I don’t know how much visibility this murder has in other parts of the country, but it is still pretty fresh in Mississippi. One reason is that Medgar’s widow, Myrlie Evers-Williams is a civil rights activist in her own right – she was on the local news just this month.

This song is unquestionably a protest song, and Bob Dylan performed “Only a Pawn in Their Game” at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the same event where Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. later gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. However, the song is really less about Evers and more about the murderer (and the other poor whites in Mississippi in those days). As Wikipedia says it: “The song suggests that Evers’ killer does not bear sole blame for his crime, as he was only a pawn of rich white elites who incensed poor whites against blacks so as to distract them from their position on ‘the caboose of the train’.”

According to Joan Baez (speaking in the documentary No Direction Home), the genesis of “When the Ship Comes In” came from Bob Dylan’s own mistreatment at a hotel when a clerk refused to give him a room. The rousing music and vivid Biblical imagery gives the song’s theme – people rising up against oppressive forces that are mistreating them – an air of inevitability that is in the spirit of the title song on the album, “The Times They Are A-Changin’”.

The structure of the song was inspired – by way of the cultural tastes of Dylan’s former girlfriend Suze Rotolo – by a Bertolt Brecht/Kurt Weill song “Pirate Jenny”; the song comes from their play, The Threepenny Opera. The song is closely associated with Weill’s wife, the Austrian singer Lotte Lenya, and her breakout role was in a 1928 production of The Threepenny Opera. The most famous song from that play is “Mack the Knife”, which was an unexpectedly huge hit for Bobby Darin in 1959. The lyrics in his version of the song even reference “Miss Lotte Lenya”. Lenya is best known to Americans for her role as the villainous Rosa Klebb in the 1963 James Bond movie, From Russia with Love.

On one of my beloved Bob Dylan bootleg albums, I have a live performance of “When the Ship Comes In” – one Internet source says that it was in Carnegie Hall – that has this memorable introduction: “I wanna sing one song here recognizing that there are Goliath’s nowadays. And, er, people don’t realize just who the Goliath’s are; but in olden days Goliath was slayed and everybody looks back nowadays and sees how Goliath was slain. Nowadays there are crueler Goliath’s who do crueler, crueler things, but one day they’re gonna be slain too. And people 2,000 years from now can look back and say, remember when Goliath the second was slain.”

* * *

About his next album, Another Side of Bob Dylan, which was released later in 1964, Bob Dylan told Nat Hentoff in New Yorker magazine: “There aren’t any finger pointing songs [here]. . . . Now a lot of people are doing finger pointing songs. You know, pointing to all the things that are wrong. Me, I don’t want to write for people anymore. You know, be a spokesman.”

His song “My Back Pages” is most direct about this new direction in his music and is blatantly self-critical – particularly in the chorus line, “I was so much older then / I’m younger than that now”. The Byrds released a version of “My Back Pages” in early 1967, the seventh and last Bob Dylan song that the band covered and released as a single.

However, this album is not devoid of his earlier musical styles either. Another Side also includes “Chimes of Freedom” that – like “When the Ship Comes In” – is rich with social commentary on the downtrodden and those who have been treated unfairly. However, to me, this is really the kind of song that Bob Dylan was singing throughout this period.

About the changes in his songwriting on Another Side of Bob Dylan, Bob Dylan told the Sheffield University Paper in May 1965: “The big difference is that the songs I was writing last year . . . they were what I call one-dimensional songs, but my new songs I’m trying to make more three-dimensional, you know, there’s more symbolism, they’re written on more than one level.” Later that year, speaking of “My Back Pages” specifically, Dylan told Margaret Steen in an interview for The Toronto Star: “I was in my New York phase then, or at least, I was just coming out of it. I was still keeping the things that are really really real out of my songs, for fear they’d be misunderstood. Now I don’t care if they are.”

* * *

In like manner, I don’t view the release of Another Side of Bob Dylan as a radical break from the past, but rather a natural evolution of his music. For that matter, I feel the same way about Bob Dylan’s “going electric” on his next two albums, Bringing it All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited; and also his Christian period in the trilogy of albums from 1979-1981: Slow Train Coming, Saved, and Shot of Love. Bob Dylan is very much undervalued as an instrumentalist, in my judgment; his guitar playing – and his harmonica, and his work as a pianist – is so strong that I often don’t even notice whether a song is acoustic or electric. As an example, until I saw it pointed out in Wikipedia while I was researching this month’s post, I had not realized that one of my Top Ten favorite Bob Dylan songs – the last and longest track on Highway 61 Revisited, “Desolation Row” – was the only non-electric song on the album.

As to his Christian period, I have already mentioned the Biblical imagery in “When the Ship Comes In”. The opening verse of the title track, “Highway 61 Revisited” on Highway 61 Revisited is a hip retelling of God’s command that Abraham sacrifice his long-awaited son Isaac. One of the songs on his very first album, Bob Dylan is a traditional folk song called “Gospel Plow”. So none of this is brand new either as I see it.

In conclusion, I am not trying to say that Bob Dylan didn’t perform protest songs; clearly he did, in the broadest sense of the term at least. However, Dylan never vented his outrage in the way that you expected, and he never went after the easy targets. While I am certainly no expert, from what I know of Woody Guthrie – Bob Dylan’s direct inspiration and even his mentor to a limited extent – much the same could be said of his music as well.

I welcome any comments that you might have on what I have written about Bob Dylan here. I suppose you could say that he has been my favorite rock artist for nearly 50 years, and I have strong feelings about his music that don’t seem to be echoed in many places. However, I was certainly gratified to find quotes from Bob Dylan himself that support much of what I am trying to say.

(May 2013)